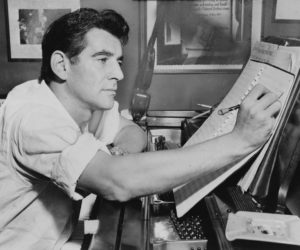

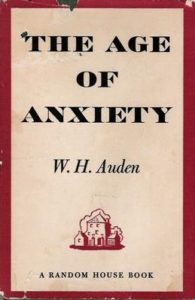

Leonard Bernstein first read Auden’s The Age of Anxiety: A Baroque Eclogue in the summer of 1947, shortly after it was published. Auden’s extravagant, book-length poem would go on to win a Pulitzer Prize in 1948, but it began to stir Bernstein’s musical imagination immediately. Between 1947 and 1949, he would compose an unconventional symphony for piano and orchestra based on it, working on it sporadically between conducting gigs and a tour through the newly created (and still unstable) state of Israel.

Poem vs. Tone Poem

The plot of the poem (such as it is) is quickly summarized. Four strangers are at a bar in New York City one night during World War II: a shipping clerk named Quant; a Medical Intelligence officer in the Canadian Air Force named Malin; a buyer for a department store named Rosetta; and an attractive navy recruit named Emble. After hearing a news bulletin over the radio, they strike up a conversation and move to a booth together. After much alcohol and a rather long and strange discussion, Rosetta invites the others back to her apartment for a nightcap, hoping that only Emble will accept. Unfortunately, they all go with her. Emble and Rosetta dance together until the others get the hint and leave, but Emble passes out. The others wander back to their places of residence as dawn breaks.

The bulk of the poem, however, is taken up with highly allusive and symbolic verse, including a rather pessimistic discussion of the Seven Ages (Auden’s updated version of Jacques’s speech about the human life cycle in Shakespeare’s As You Like It) and an imaginary journey through a dreamlike landscape of the subconscious mind (which rather resembles England) that Auden refers to as the Seven Stages. This section of the poem is so opaque that even Auden experts have yet to decipher its meaning. Complicating matters is the fact that the characters are apparently allegorical representations of various mental faculties from Jungian psychology (intuition, thinking, feeling and sensing). The poem seems to be a meditation on the psychological implications of living in the modern world (especially in the context of World War), and concludes by suggesting a turn to religious faith. Critical reception of the poem has been decidedly mixed in the years since it appeared.

These complications did not seem to trouble the Harvard-educated Bernstein, who called the poem “fascinating and hair-raising…one of the most shattering examples of virtuosity in the history of British poetry.” As with Plato’s Symposium, which would later inspire his Serenade, he was likely attracted to The Age of Anxiety because of its homoeroticism. While it is not nearly as explicit as Plato’s Symposium, there are a few veiled references to homosexuality in the poem. More importantly, though, was that Auden himself was gay, a fact Bernstein likely knew. As with the Serenade (after Plato’s Symposium), intellectualism was likely to some degree a mask for Bernstein’s expression of his own homosexuality. In the context of the early days of the Cold War and McCarthism, it may also have been a mask for the anxiety many artist felt at the dawn of the nuclear age.

Bernstein would claim that “No one could be more astonished than I at the extent to which the programmaticism of this work has been carried…when each section was finished, I discovered, upon re-reading, detail after detail of programmatic relation to the poem…” Bernstein revealed few of those correspondences, but the following discussion attempts to piece together the music and the poem as much as possible.

Prologue and The Seven Ages

The piece begins with an “echo tone” duet for two clarinets in a quasi-improvised style:

The poem begins with Quant staring into the mirror behind the bar, wondering if life is better for the mirror version of himself than it is for him; perhaps the duet symbolizes Quant and his reflection. It is also interesting to note that Bernstein recycled this music from incidental music he wrote in college for Aristophanes’ The Birds. He described it as “The loneliest music I know.” We then hear a downward scalar figure, which Bernstein tells us “acts as a bridge into the realm of the unconscious, where most of the poem takes place.”

The entrance of the soloist marks the beginning of the next section: The Seven Ages. Together with the following section, The Seven Stages, it consists of what Bernstein describes as “a series of variations which differ from conventional variations in that they do not vary one common theme. Each variation seizes upon some feature of the preceding one and develops it, introducing, in the course of the development, some counter-feature upon which the next variation seizes.” The music in effect has the episodic, cyclical feeling of a theme and variations, though each “variation” is in fact a kind of miniature character piece.

The first variation corresponds with the first age, infancy through early childhood.

Behold the infant, helpless in cradle and

Righteous still, yet already there is

Dread in his dreams at the deed of which

He knows nothing but knows he can do

Musically, it is a simple, almost chorale-like solo for the piano that ends with the reappearance of the descending scale that leads to “the realm of the unconscious.”

The second variation depicts the second age, adolescence:

…threatened from all sides,

Embarrassed by his body’s bald statements,

His sacred soul obscenely tickled

And bellowed at by a blatant Without,

A dog by daylight, in dreams a lamb

Whom the nightmare ejects nude into

A ball of princes too big to feel

Disturbed by his distress, he starts off now,

Poor, unprepared, on his pilgrimage

To find his friends, the far-off élite

This variation features a descending piano figure that in context is seems a development of the descending “unconscious” scale. It begins quietly, but soon becomes more agitated before fading into the next variation.

The third age is young adulthood. The characteristic feature of this age seems to be disappointment with sex:

…he learns what real

Images are; that, however violent

Their wish to become one, that wild promise

Cannot be kept, their case is double;

For each now of need ignores the other as

By rival routes of recognition

Diminutive names that midnight hears

Intersect upon their instant way

To solid solitudes, and selves cross

Back to bodies, both insisting each

Proximate place a pertinent thing.

So, learning to love, at length he is taught

To know he does not.

Note the lack of any reference to a female partner. The pianist is silent for this variation. Instead, it features a lushly scored melody above a plodding, walking bass line. The melody was recycled from an unpublished violin sonata Bernstein wrote in 1940.

The fourth age seems to feature the rat race and the abandoning of youthful ideals in favor of various dogmas:

Now unreckoned with, rough, his road descends

From the haughty and high, the humorless places

His dreams would prefer, and drops him till,

As his forefathers did, he finds out

Where his world lies…

Signs and insignia decide our cause,

Fanatics of the Egg or Knights sworn to

Die for the Dolphin, and our deeds wear

Heretic green or orthodox blue,

Safe and certain.

The music features a sprightly, whirring rhythmic figure in 5/8 in the piano that is at times interrupted by a more strident idea in the strings.

The fifth age corresponds to the attainment of either hollow middle-aged respectability:

In peace or war,

Married or single, he muddles on,

Offending, fumbling, falling over,

And then, rather suddenly, there he is

Standing up, an astonished victor

Gliding over the good glib waters

Of the social harbor to set foot

On its welcoming shore where at last

Recognition surrounds his days with

Her felicitous light.

Or alternatively disappointment:

…Will nightfall bring us

Some awful order—Keep a hardware store

In a small town….Teach science for life to

Progressive girls—? It is getting late.

Shall we ever be asked for? Are we simply

Not wanted at all?

Those professions apparently did not appeal to Auden. Bernstein writes loud, fast, mad circus music full of Shostakovich-like sarcasm.

In the sixth age, the body begins to decline and people begin to feel nostalgic for an idealized memory of youth:

Our subject has changed.

He looks far from well; he has fattened on

his public perch; takes pills for vigor

And sound sleep, and sees in his mirror

The awing genius of a jackass age,

A rich bore.

…He pines for some

Nameless Eden where he never was

But where…

…the children play

Nor care how comely they couldn’t be

Since they needn’t know they’re not happy.

…

So do the ignored. In soft-footed

Hours of darkness…

…Pride lies

Awake in himself too weak to stir

As Shame and Regret shove into his their

Inflamed faces, we failures inquire

For the treasure also.

This variation is for the pianist alone, and consists of rather dissonant, twitchy music. Bernstein indicates that it should be played “quasi cadenza”—“like a cadenza”—and midway through “con tristezza”—“with sadness.”

The final stage is extreme old age, accompanied by the failing of the mind and body.

His last chapter has little to say.

He grows backward with gradual loss of

Muscular tone and mental quickness:

He lies down…

…and he years only

For total extinction….

After a melancholic duet for oboe and English horn that somewhat recalls the opening melody of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, the piano brings back the downward scale into the unconscious, leading to what Bernstein calls the “inner and highly symbolic journey” or “dream-odyssey” of the Seven Stages. Apart from the reappearance of the downward scale, the Seven Stages are represented by more “variations” continuous with those of the Seven Ages.

The Seven Stages

In the first stage, the four characters imagine themselves near the shores of a misty lake. They then hike up to a mountain pass. The music features a rocking melody above a heavy, walking bass line.

In the second stage, the characters travel from the mountain pass to two different seaside ports in pairs, Malin and Quant together in a car and Emble and Rosetta by foot. This variation is marked “Tempo di Valse” in the score, and has a playfully erratic, waltzing character, alternating charming quiet passages with more unsettling loud ones.

The third stage has the pilgrims of the unconscious travel from the seashore to a great metropolis that resembles London. They go in pairs again, Malin and Quant by train and Emble and Rosetta by plane. Those on the train see various unappealing types making their way to the city (“The successful smilers the city can use”) while those on the plane feel liberated by their distance from the landscape rushing by below them. The music begins softly with a somewhat ungainly idea in the piano. When this melody is transferred to the woodwinds, the piano plays filigree around it marked “lusingando” or “flattering.” The variation is essentially a crescendo that builds as more instruments take up the melody.

In the fourth stage, the characters travel through the city on a commuter rail line heading north through the suburbs, observing such sights as a women’s prison and a “…whitewashed/Hexagonal Orphanage for/Doomed Children…” Eventually they arrive at a “big house” that resembles the grand country houses featured in English murder mysteries (Auden was a whodunit addict). This variation is a bit more contrapuntal, featuring two-voice counterpoint somewhat in the style of a Bach invention. Expressively, it seems to become increasingly agitated.

In the fifth stage, the characters run a race from the big house to a graveyard. The characters’ thoughts as they run are meant to reveal their psychology:

Thus MALIN mutters:

‘Alas,’ say my legs, ‘if we lose it will be

A sign you have sinned.’

And QUANT:

The safest place

Is not the more or less middling: the mean average

Is not noticed.

And EMBLE:

How nice it feels

To be out ahead: I’m always lucky

But must remember how modest to look.

And ROSETTA:

Let them call; I don’t care. I shall keep them waiting.

They ought to have helped me. I can’t hope to be first

So let me be last.

This variation is a quick, brief, sparkling dance for the piano with only the lightest accompaniment from pizzicato violins and flutes. It runs directly into the next variation.

In the sixth stage, they travel from the graveyard to the hermetic gardens, once again in pairs, but this time Rosetta with Quant and Emble with Malin. Emble and Rosetta seem disappointed that they are not together again, but Malin seems to enjoy Emble’s company quite a bit:

…my hunger for a live

Person to father impassions my sense

Of this boy’s beauty in battle with time.

Emble later responds: “Unequal our happiness: his is greater.” We are told that they are traveling west by bicycle while Rosetta and Quant are traveling east by rowboat. They all wind up at the same place anyway. Musically, the patter of the piano solo continues as the contrabassoon and tuba introduce a slower, more menacing idea below. The piano peters out as the other idea grows more intense in first the brass then the full orchestra.

In the seventh stage, the hermetic gardens turn out to be so lovely that they inspire feelings of unworthiness in the characters, who wander separately into a dark forest until they reconnect. They then leave the forest to face an inhospitable wilderness. Each of them journeys to one of the four corners of the Earth (north, south, east and west), but they find only images of war and destruction. They then return to the conscious world of the bar in midtown Manhattan. The music provides a wild, frenetic finale to Part I of Bernstein’s symphony.

Part II – The Dirge, The Masque and Epilogue

Part II is comparatively straightforward. During the cab ride back to Rosetta’s apartment, the characters yearn for some paternal figure—“some Gilgamesh or Napoleon, some Solon or Sherlock Holmes”—to save humanity from itself and the natural world. They are pessimistic about this possibility, however, as “long or lately” such characters have “always died or disappeared.” They thus express their grief at this loss through a dirge:

…Mourn for him now,

Our lost dad,

Our colossal father.

This is effectively the slow movement of the symphony. The piano begins it by slowly arpeggiating a dissonant chord that contains all twelve notes of the chromatic scale. Woodwinds and harp respond with music reminiscent of “The Evocation of the Ancestors” from Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. The piano and piccolo then begin a high-pitched melody on top of this. The twelve-note arpeggios return at a faster tempo when the strings enter, building to a loud statement for full orchestra. A contrasting middle section focused on the piano ensues, until the twelve-note arpeggio returns in a brutal orchestral climax. The dirge dies away as other melodic ideas return, leading directly to the next section: The Masque.

After the foursome arrives at Rosetta’s apartment, they turn on the radio, and Rosetta and Emble dance. Auden notes that in times of war, even the most fleeting amorous encounters take on a special air of significance. Rosetta and Emble even exchange mock marriage vows.

The music features Bernstein’s trademark jazz-influenced style. He described it as “by turns nervous, sentimental, self-satisfied, vociferous.” The piano is only accompanied by percussion, harp and celesta. The tuneful melody that appears periodically was actually recycled from a rejected number from On the Town called “Ain’t Got No Tears Left.”

The Masque ends when the orchestra enters, leaving the piano “traumatized.” In a theatrical gesture, a pianino in the orchestra continues playing afterward while the soloist remains silent, representing “a kind of separation of the self from the guilt of escapist living…” The soloist/protagonist is then “free again to examine what is left beneath the emptiness.”

“What is left, it turns out, is faith,” Bernstein says. In Auden’s poem, the Masque section ends after Rosetta escorts Quant and Malin to the elevator and returns to find Emble asleep, when she has an extended meditation on her Jewish faith, which some have read as Auden’s response to the holocaust. The epilogue then concludes with Malin’s thoughts on his Christian faith.

In the original version of the piece, Bernstein had the piano soloist remain silent throughout the epilogue until the final chord. Pianists, however, did not seem to like this much, so in 1965 he rewrote the ending to give more music to the piano, including an extended cadenza that recalls themes from earlier in the piece. The pianino even interjects, but the soloist is not lured by its escapism. The piece ends with a glowing, affirmative orchestral crescendo (a bit reminiscent of the finale from Ravel’s fairytale Mother Goose ballet) which is joined by the piano for the final chord.

Regarding the original version, Bernstein remarked that the faith it expressed was “strictly Warner Brothers,” and indeed, the style of the music is somewhat cinematic. Originally he wanted the pianist to remain silent, perhaps not fully convinced of this uplifting expression of faith, though the revised version brings the pianist closer to it.

Bernstein dedicated the score to his mentor, Serge Koussevitzky, who conducted the premiere with Bernstein at the piano in 1949. Bernstein would perform it and the revised version many times throughout his career, both as soloist and as conductor. With its irony, stylistic quotation and endless layers of programmatic meaning, Bernstein’s symphony expresses a postmodern aesthetic decades ahead of its time. Instead of providing reassuring answers, it poses difficult questions. As resonant today as it was in 1949, it suggests that we are perhaps still living in an age of anxiety. —Calvin Dotsey

Don’t miss Bernstein’s The Age of Anxiety (Symphony No. 2) this Easter weekend, March 29, 30 & 31. Get tickets and more information at houstonsymphony.org.